A good job interview sets both sides up for success

Over the past few weeks I've ended up in a lot of discussions about job interviews in tech industry. I've talked with people doing interviews, I've talked about my experiences and opinions on interviews and I've talked with a lot of juniors, trying to give them some advice on how to best play the interview game. Because that's what it often unfortunately is.

One common thread popped up in many discussions that I feel very strongly about: I think a good job interview sets both up for success. I think that's something a lot of people can agree with so I wanna dig a bit deeper on what I mean by a good or a bad interview. Especially, I hate when a job interview is a game with hidden rules.

The Game with Hidden Rules

What do I then mean by these hidden rules? Any given job interview is relatively strapped with time: most interviews I've taken part have been between 30 and 60 minutes each. That means that if there's any given task, especially a technical one, given to the applicant, tradeoffs must happen. And when the interviewer keeps hidden which tradeoffs they want to see, we enter a realm where job interviews become minefields of traps and quite frankly, it's unlikely you find the best people.

Let's say there's a technical task in an interview to implement an LRU cache. An interview situation is not real life production development, there's even more tradeoffs to be made than usual: should you write tests, how extensively should you document it, what assumptions can you make, how much optimization should be done and so on.

Now the response to that is often: I want a good senior to ask these questions and have a discussion. And that's great if it is. But given that interview is kinda like a game, it might be that another interviewer is more interested in your technical implementation skills and as an applicant, you need to make a guess which one your interviewer is.

I think those kind of guesses should not have to happen in an interview. For example, you could on the other hand end up discussing those questions with your interviewer for a good chunk of time, eventually running out of time to actually implement things and depending on what the hidden rules were, you might be disqualified because you spend too much time on talking.

And that's why I'm so passionately against putting the candidate into a position where they need to guess which kind of questions and which kind of answers the other party is looking for.

Another look into the same problem

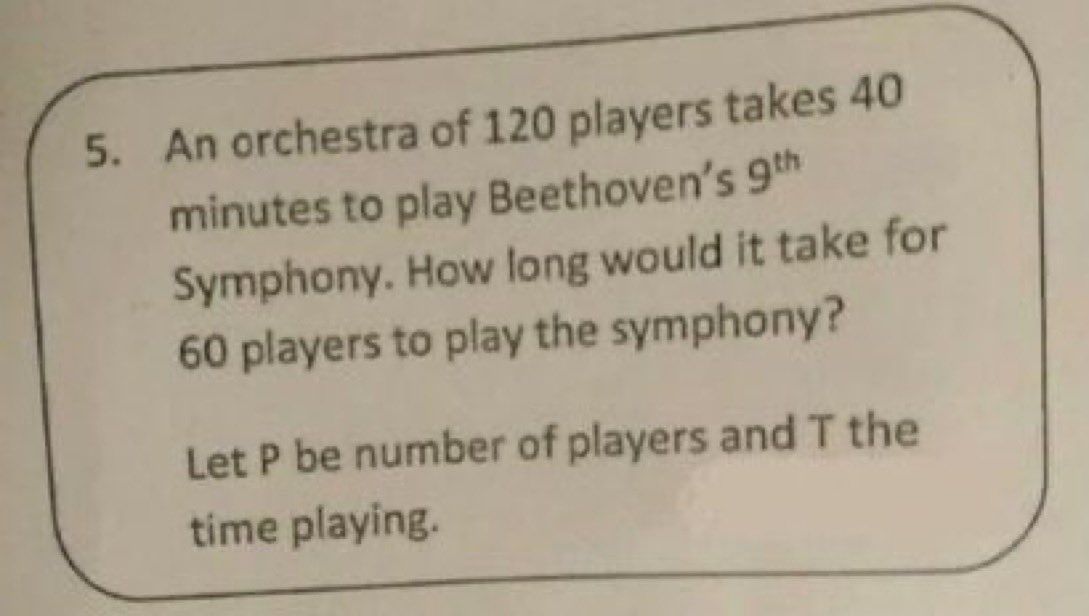

I saw this picture on Twitter the other day with accompanying text

"This is an excellent question and the number of supposedly smart people thinking it’s intended as a “plug numbers in formula” question makes me very sad"

I think this is exactly the type of situation that the hidden rules in job interviews are too. I do agree that it's important when learning mathematics to also understand that once you have a hammer, things might look like nails but you need to be careful.

But if the context of that is a math exam, I'd argue it's a really bad question. First, because during an exam we're in an artificial environment where expectations are that we are testing math skills. I've seen so many times when these kind of math questions with written stories are so inaccurate and maybe the person who wrote it knew less or from different culture than the one reading and solving it.

It might be that the "correct" answer to question above is 160 minutes. It's very possible that being a "smart ass" and pointing out that in real life, adding or removing players doesn't affect the length of the play could disqualify you.

I still remember in high school when a friend of mine was deducted points in a math question because he pointed out that a 0-minute taxi drive does not cost 0 euros because there's a starting cost for every ride. The teacher didn't agree with that, claiming that real-life circumstances were not part of the question and should not be brought into the equation.

Of course, it's just an anecdote but that's kinda the point. When we do math exams or job interviews, we're few degrees separated from the real world because they are artificially simplified situations.

A good interview sets up for success

I firmly believe that setting up trick questions to see where the other party fails because they didn't think the same simplifications/abstractions as you did as an interviewer, are not beneficial to anyone.

A good interview sets up expectations and frames up the situation better so that the discussion can focus on figuring out if the skills of the candidate match the needs of the company and role as well as figuring out if what the company is looking for and can offer, matches what the candidate is looking for.

Making your candidate guess what the parameters are, is not a good or necessary way to assess skill level. And if they end up asking about all of those trying to discover the parameters, it's likely they won't have time to actually code and the interviewer might come to the conclusion that the candidate only talks tech but can't code or isn't focused enough on deliverables.

None of this means that you can't ask difficult questions or try to find the boundaries of candidate's skills. You absolutely can and most cases should. But playing tricks is kinda like randomly throwing out 50% of the applications and say "it's unlucky to be discarded randomly and I don't want people who are unlucky". It's not based on anything real and it does not set up for a good relationship either.

In general, job interviews should be about finding good matches – or invalidating those assumptions – so that both sides can move on, either together or separately.

My best interview experiences

There are a small handful of really good interview experiences I've had as a candidate – some that lead to a job and others that did not. The common thing in all of those has been that we've both been excited about the topic and ended up having great discussions. Less exam-style questions and answers but deep discussions about developer relations, community building and technology. I also believe they can be more effective because it's harder to "cheat" or practise answers up front when you end up having a proper discussion.

In one interview for a developer advocate role a few years ago, me and their current developer advocate just ended up geeking out and chatting about why developer advocacy is so cool for an hour or so. I don't think a single interview question was asked during that time. I ended up also making a new friend in the industry despite eventually not continuing the process with them.

In another more recent one, we started in a rather interview-y style but quickly we realized that we share a lot of thoughts and ideas but also had good disagreements on certain topics and that led into a discussions that got me really excited (and honestly, I really wanted then to work or collaborate with that person one day).

One interview I finished by recommending a few people I knew in the industry because I realized it wasn't a great match for what I was looking for at the time. Thus we mostly just talked about how to approach developer relations for a company like theirs and it turned out to become more of a brainstorming session between professionals than an interview.

A developer candidate might not remember some Javascript standard library implementation details off the top of their head in a nervous interview situation (I'm horrible at these kind of tasks) but if you can have a in-depth discussion about a project they did and tech choices they made and how they would change the architecture or make different choices and why, I'm convinced you get much better insights into their skills as a software developer.

Not related to an interview but this Monday I had a great discussion in a Rust meetup about how I had planned to start building a static site generator with Rust as a learning project but ended up not figuring out how to architecture the plugin system because I'm so used to dynamic languages where I could just run any code from plugin library and less used to compiled software as is the case with Rust.

Now, that discussion was a great one and I think even though it wasn't the goal of the discussion, the person I was chatting with probably got quite a good idea of where my strengths and skill limitations with the specific language but also with software development in general are. Had that been an interview discussion, I would have been really happy about the outcome. Not because I succeeded to wow someone with my impeccable Rust skills but because I felt that this discussion let me frame my skills and understanding in a very realistic way – without having to guess what my skills are on a scale from 1 to 10.

Interviewing is hard

I know recruitment and interviewing is hard. Building an internal system that gives different people an equal opportunity without becoming a rigorous exam quiz is hard. But that's probably why the good ones really stand out.

In interview is a two-way street. As much as it exists for the company to assess the skills of a candidate, it's also a place where the candidate has an opportunity to assess the company for a good fit and opportunity. And for me, a good interview has always been a really strong selling point – or a red flag in some cases.

If something above resonated with you, let's start a discussion about it! Email me at juhamattisantala at gmail dot com and share your thoughts. In 2025, I want to have more deeper discussions with people from around the world and I'd love if you'd be part of that.